Leslie Johnson wrote this manuscript between 1974 and 1979. It records the BIS story during the Liverpool years. It includes his reflections on their collective 1930’s dream realised in 1969 – the landing on the Moon of Apollo 11. This book (paperback and ebook) includes a foreword from his daughter Pam Reid, an introduction and an epilogue from me. An excerpt from my epilogue is below and “look inside” images of the book, at the bottom.

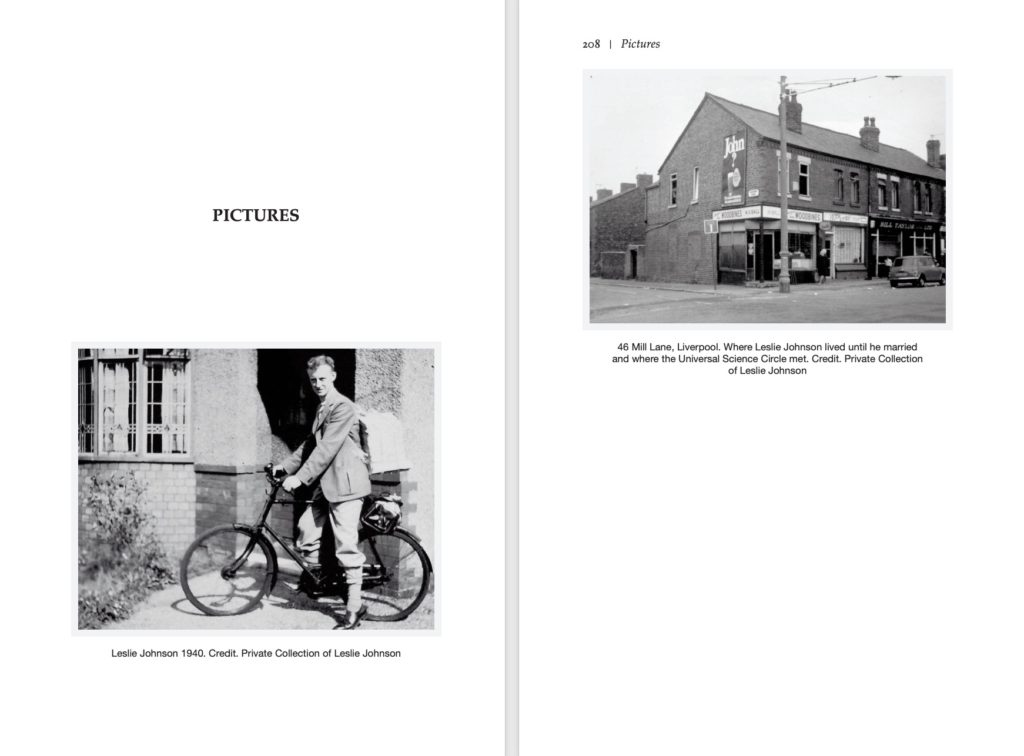

Most of the early BIS members were writers. Post-war members included Carl Sagan, Eric Burgess, Olaf Stapledon, George Bernard Shaw, Robert Heinlein and Patrick Moore. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, Willy Ley and Isaac Asimov were considered “Astrofuturists”. They were all scientifically literate, and scientific principles guided their writings. Many of the visions they imagined then underpin our 21st-century society today. For example, the focus of Clarke’s celebrated 1945 paper, ‘Extraterrestrial Relays’, is now deployed in communication satellites that provide communication services anytime, anywhere between anyone on Earth. In 1971, Clarke was invited by the US State Department for the signing of the 80-nation INTELSAT (International Telecommunication Satellite Organisation) agreement. He concluded his speech by saying, “you have just signed far more than just another intergovernmental agreement. You have just signed a first draft of the Articles of Federation of the United States of Earth”. By chance, in 1975, when he was living in Sri Lanka, Clarke was one of the first to have a private satellite link at home. In his 1973 novel, Rendezvous with Rama, Clarke imagined a human society living in colonies amongst the solar system’s planets. Rather than a World State, he imagined a United-Nations-like body but for all the colonies of the Solar System. He called it United Planets and based its headquarters on the Moon. Johnson, Cleator, Clarke and all their contemporary writers were innately optimistic and shared principles of Humanism. In October 1939, Cleator described war as the “supreme and ultimate imbecility of the human species”. Rather than undermining their pre-war naive desire for a utopian future for humanity, their first-hand experiences of war vindicated their belief in a peaceful future for a united human race empowered by spaceflight. The interplanetary community wrote about a future in which their hopes and wishes of the 1930s would be an everyday reality. A utopian vision where space technology could deliver education, fresh food, medical needs, social interactions and intellectual fulfilment. Much of the imagined technology has arrived, but these benefits are not yet equally distributed to all the people on the planet. That technology allows more people to live longer, healthier lives for the first time in human history. Still, poverty, discrimination and gross inequality persist within and between nations. An unassuming young man from Liverpool, born in the year the First World War started, Leslie Johnson not only lived through a remarkable period in history but also made a personal contribution to it. As a teenager, he established the Universal Science Circle. He does not write about the thought processes that led him to create it. He did not explicitly express his aspirations for a peaceful world united by a single international language powered by modern technology. But all his contributions convey that vision. It is a vision far from being realised, but incremental progress towards it continues to be made.

Leave a Reply