The James Webb Space Telescope has already wowed astronomers and the general public with some incredibly spectacular deep space images. But did you know, NASA has set aside a substantial number of hours for JWST to observe the objects in the solar system? What’s more that programme kicks in this autumn so some images of planets and their moons along with asteroids and comets will be published before the end of this year.

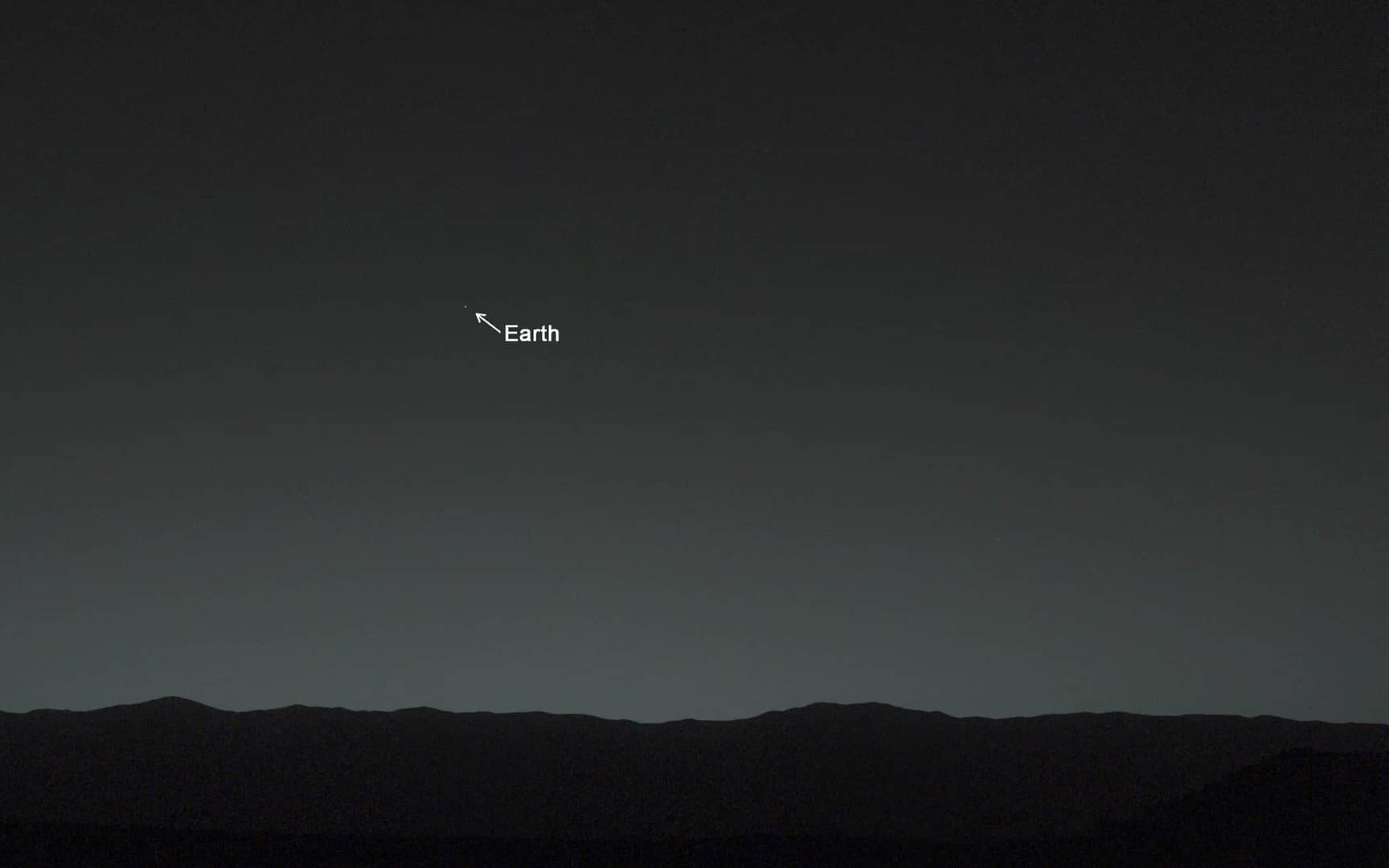

A team of astronomers including planetary scientist Dr Connor Nixon will make use of the Guaranteed Time Observations (GTO) to observe the objects in the solar system from Mars and beyond. JWST cannot look towards the Sun so excludes the Earth, Venus or Mercury. The program is led by Dr. Heidi B. Hammel.

In this interview recorded in July during COSPAR2022 in Athens, Connor Nixon talks about the GTO and his role in it looking at Titan.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 35:21 — 28.3MB) | Embed