This piece was first published in Manchester Histories blog on 12 April 2023

On Wednesday, 12th April 1961, a bright and sunny spring morning, an air force pilot of the USSR launched into space using a modified intercontinental ballistic missile. On his first trip outside the USSR, Yuri Gagarin, aged 27 went -around the world in just 90 minutes. He broke the world altitude and speed records. He was the first to experience the realm and sensation of being in space. Exactly three months later, he came to Manchester.

He arrived at Ringway airport at around 10am on Wednesday, 12th July and travelled first to the Headquarters of his hosts, the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers (AUFW) in Old Trafford. It was a sunny day but peppered with occasional sharp showers typical in July. Thousands lined his route from Ringway to Old Trafford. Travelling in an open-top Bently, he received a true Mancunian welcome. He was soaked. In the small union HQ, he was made an honorary member of the AUFW and President Fred Hollingsworth presented him with a medal engraved with the words “Together, moulding a better future”.

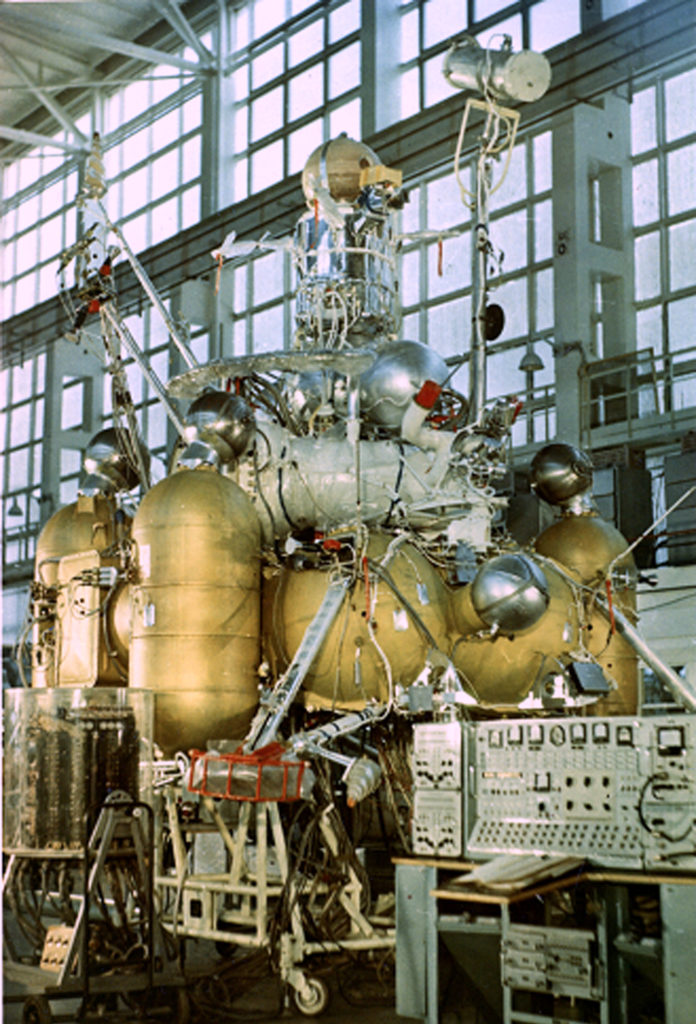

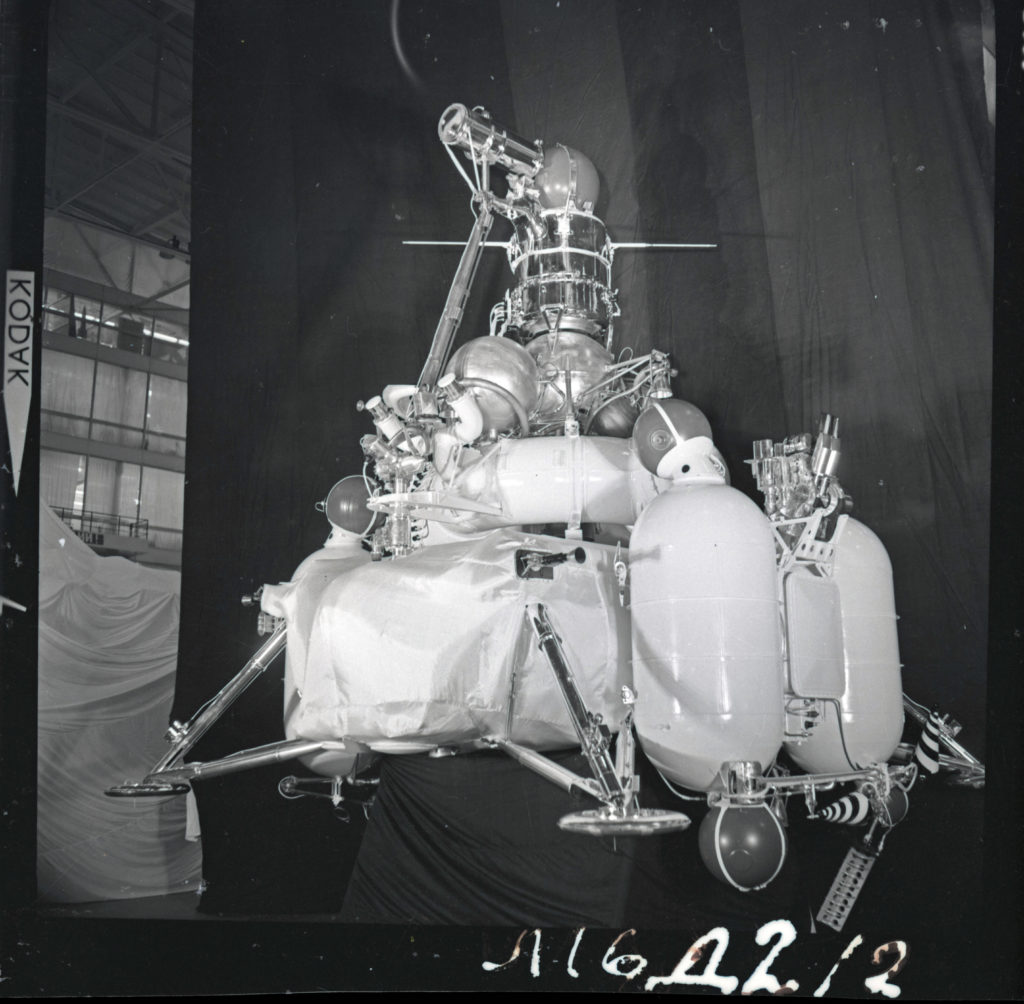

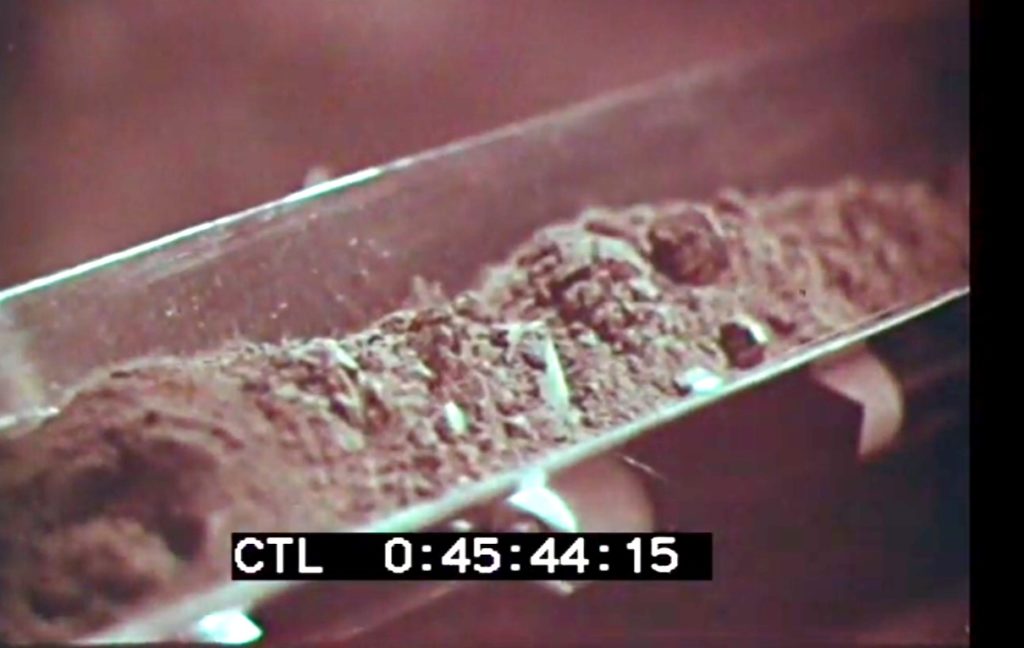

His second stop was Metropolitan Vickers in Trafford Park, a unique place in Machester’s history of the industrial revolution. By now, the rain had stopped but puddles hinted at the recent downpour. Stanely Nelson recalled shaking Gagarin’s hand near the foundry. He recalled the working conditions most foundry workers endured saying, “it was like a vision of hell. Smoke, fire and tiny thin men silhouetted against the foundry fire. No one was fat; they were all thin like Lowry’s match stick men”. Of all his time in Britain, it was this time surrounded by working men and women amongst the dirt and grime of a working foundry that Gagarin would later say he felt most at home.

He arrived at Manchester Town Hall for a formal civic reception hosted by the Lord Mayor. Albert Square and all the surrounding office windows and doorways were crammed with people waiting to see the only man with the experience of Earth orbit. The dignitaries who got to shake his hand included Bernard Lovell from Jodrell Bank and the mathematician Kathleen Ollerenshaw. At the Town Hall, Gagarin, speaking in Russian, expressed his wishes for future space missions saying, ”I would like naturally like to fly to the Moon then perhaps to Mars and Venus and even further if my abilities make it possible”. By 16:30, he was at Ringway on his flight back to London, where he had arrived the day before and would stay until his return flight to Moscow on Saturday, 15th July.

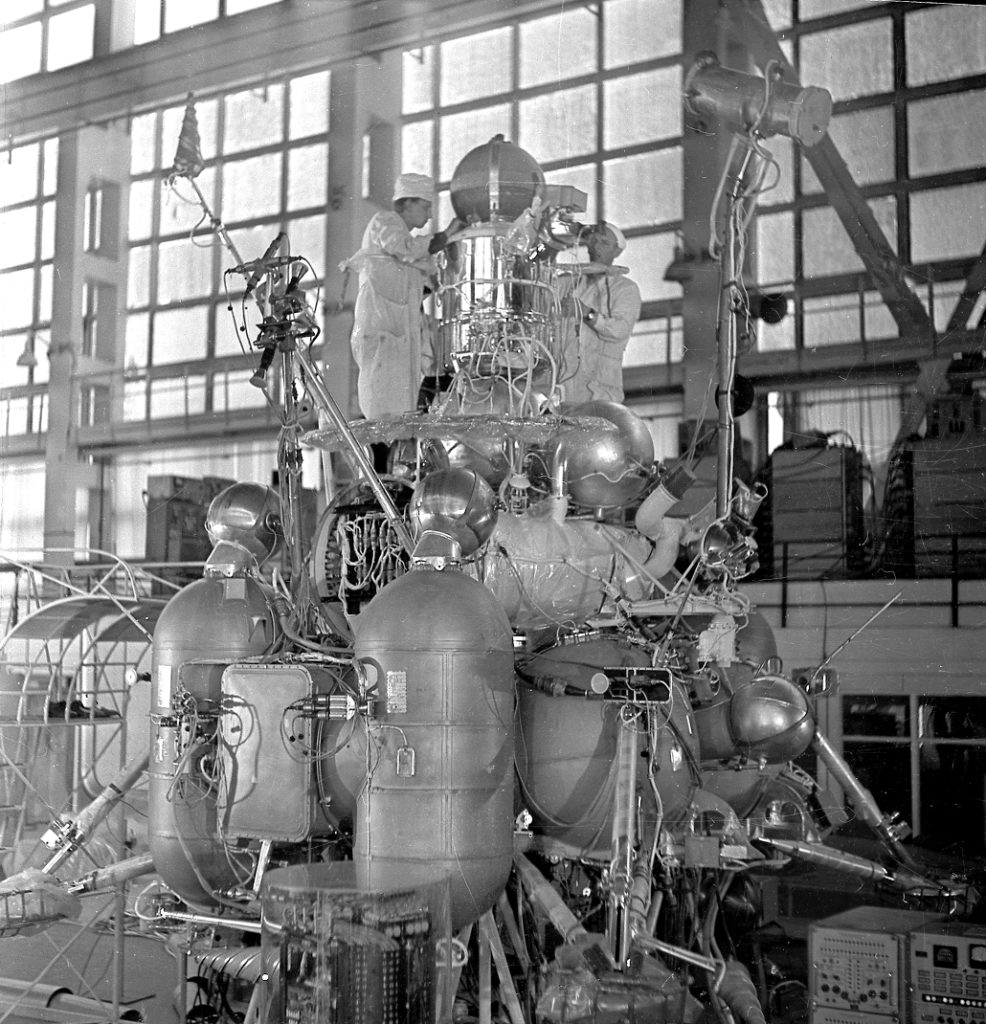

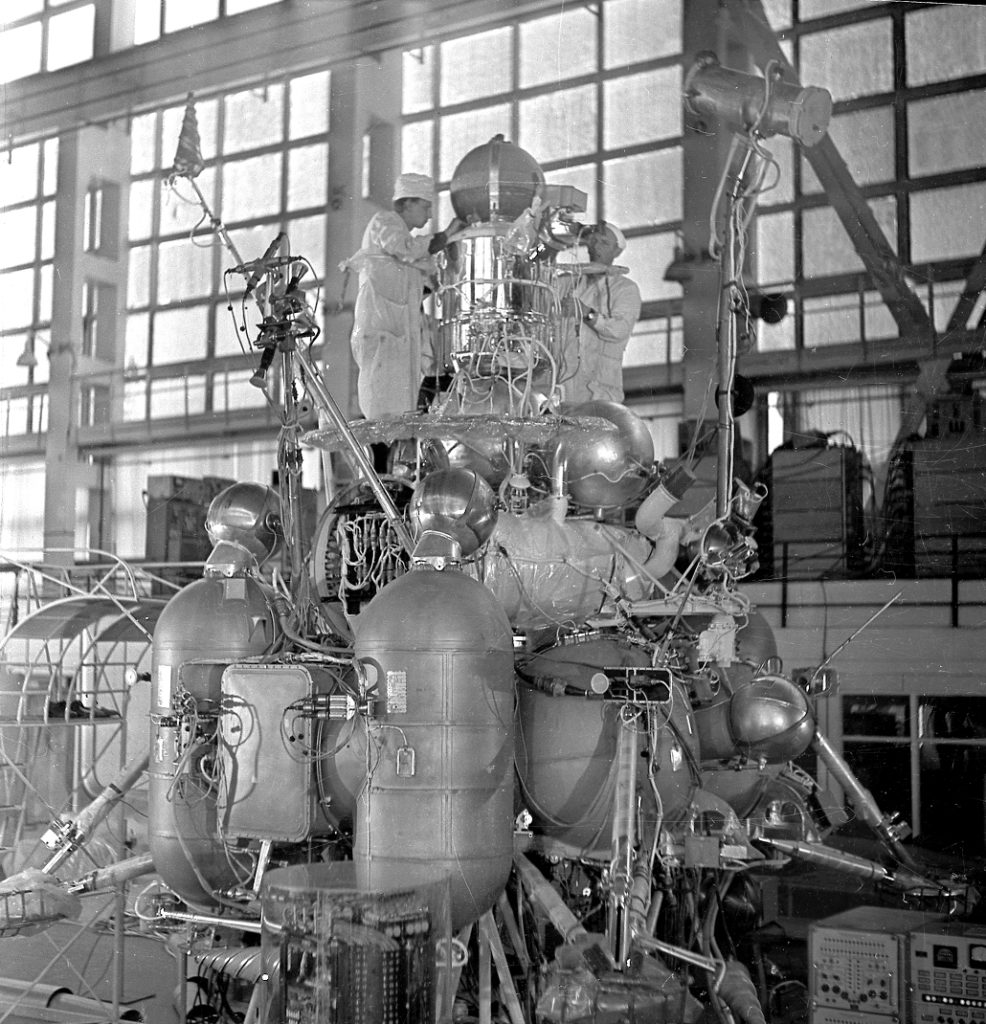

His spaceflight was packed with risk. He had left his wife a letter saying that should he not return, a real possibility, she should not remain alone. He experienced problems at launch and another during re-entry. The service module separation did not go to plan. The mission and his life came close to a catastrophic end. Ejecting from his spacecraft and landing separately by parachute, he returned to Earth as a real-life superhero. It was a supreme technological triumph, fulfilling humanity’s age-old dream of leaving Earth. It was achieved by a nation championing the virtues of communism in the midst of the Cold War. This was his first visit to the heart of the democratic West to demonstrate the prowess of the communist way of life.

To avoid highlighting the USA’s failure (its ally) to “be the first”, the UK government could not offer Gagarin a formal invitation. The remarkable response on his first day in London on 11th July, the public turned out in their thousands lining the streets in London and inundating Earls Court, the venue of the Soviet Trade Fair. Before the day was out, he had received an invitation from the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan and the Queen. His initial two-or-three-day UK visit was extended to five.

Following the global coverage of his flight in April, AUFW President Fred Hollingsworth discovered that Gagarin had trained as a Foundry Worker. It was the invitation the AUFW made in May of 1961 that brought Gagarin to Manchester. Gagarin met the Prime Minister at the Admiralty and the Queen in Buckingham Palace, along with other visits to the Air Ministry, Mansion House and the Royal Society at Burlington House. In April 1962, the first anniversary of his flight, Gagarin sent a message to the people of Manchester saying, “And the firm handshakes of my fellow workers in the moulding shop were dearer to me than many awards”. For the many who saw or met Gagarin recalled his charm, good looks and his persistent smile.

Gagarin’s visit coincided with the heightened risk of another world war. The Bay of Pigs invasion, the end of the ban on nuclear weapons testing, the building of the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis. He was probably aware of the rising geopolitical tensions more than most. While in Manchester and London, Gagarin repeated his message of peace. Despite his extraordinary achievement, the people of Manchester saw an ordinary man with humble roots. For most, he was probably the only individual from the USSR they would ever meet.