This review first appeared in The Space Review on 30 August 2021.

Title European-Russian Space Cooperation

Author Brian Harvey

Publisher Springer Praxis Books

The Cold War was primarily the story of the USSR and the USA and their respective allies. By chronicling in meticulous detail European-Russian Space cooperation, Brian Harvey has uncovered a strategic relationship between France and the USSR that modulated the larger USSR/USA Cold War relationship that dominated geopolitics between the end of WW2 and demise of the USSR in 1991. It is not just about historical events. The final chapter illustrates the same geopolitical forces are at work shaping international cooperation in space today with the turbulent story of ExoMars.

Harvey starts the first chapter, as the title would dictate with de Gaulle arriving in Moscow in June 1966 as President of France. De Gaulle’s connections with Russia started back in WW1 as a POW in Germany alongside Mikhail Tukhachevsky who later became one of Stalin’s marshals. De Gaulle’s first visit to Moscow was in 1944 then representing the Free French movement. In addition to this deep-rooted connection with Russia, de Gaulle considered the “Special Relationship” between UK and USA as subservient and ensured France did not follow. Re-elected in 1965, de Gaulle used his fresh mandate to reassert French independence and withdrew France from NATO command in March 1966 just three months before his arrival in Moscow. These conditions set the path for France and later Europe on their unique collaboration in space that persist to this day.

The book traces collaborative space projects between USSR/Russia with Britain (Jodrell Bank tracking and communication), Germany and its specialisation in X-ray astronomy (Spectre RG project), Italy spacecraft manufacture (most recently ExoMars – Trace Gas Orbiter and lander Schiaparelli) and the several formerly Eastern bloc countries (i.e. Hungary, Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia and East Germany) which took advantage of the existing cultural connections with scientific and industrial institutions in the Soviet Union where the scientist and engineers spoke Russian.

Reminiscent of Gagarin’ visit to the UK five years earlier, de Gaulle‘s 1966 USSR visit was marked not only by the motorcycle escort and hordes of public that lined

Gaulle’s route. A visit to Baikonur (first by a representative of the west) and a hotline by between the Kremlin and the Elysée palace illustrated that both sides were committed to a deep and long relationship.

The agreement to collaborate in space was signed on the 30 June 1966. Half a century later, its success can perhaps be traced to the fact that it was signed alongside another for scientific, technical, and economic cooperation. This broader and deeper commitment facilitated establishing multiple complex projects between peoples from differing cultures, politics, and languages. It was a “miracle that the Franco-Russian cooperation survived this test” says the author. It survived because key ingredients were established at the outset including annual reunions, long term high-level political support, patience, mutual good-will and picking the right kind of projects to work on.

The book’s 400 pages deals with collaboration in scientific, industrial, human spaceflight and ExoMars in six chapters. The story of collaboration is largely a USSR-European programmes but led and facilitated by France. In parallel, many of the same European countries were engaged in separate collaborative projects with the USA too. With some exceptions, there was largely no cooperation in space between the USA and USSR.

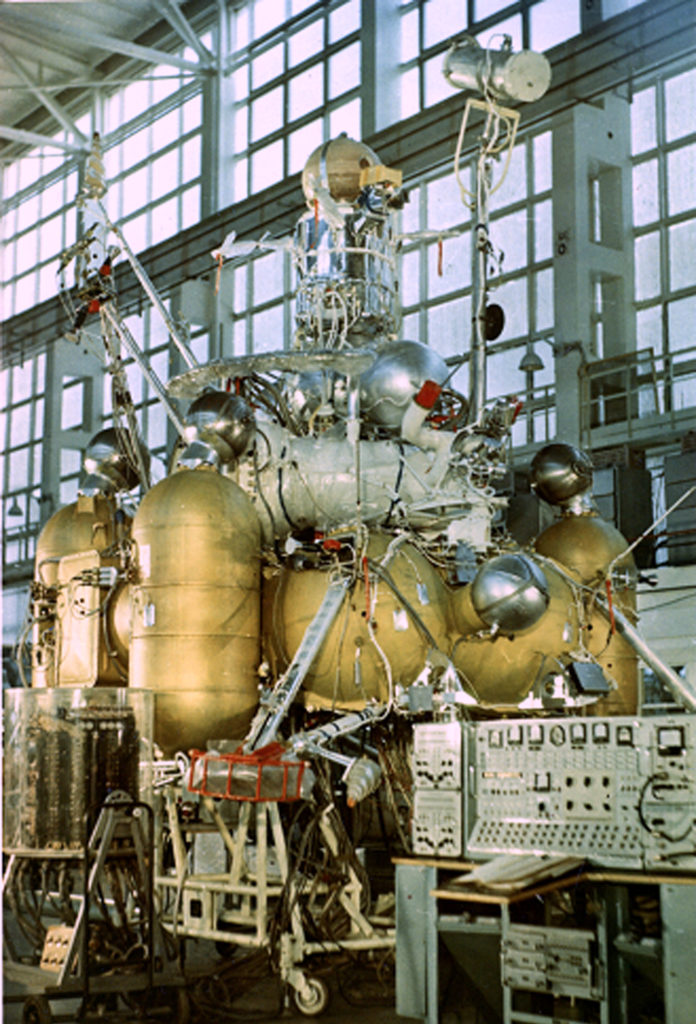

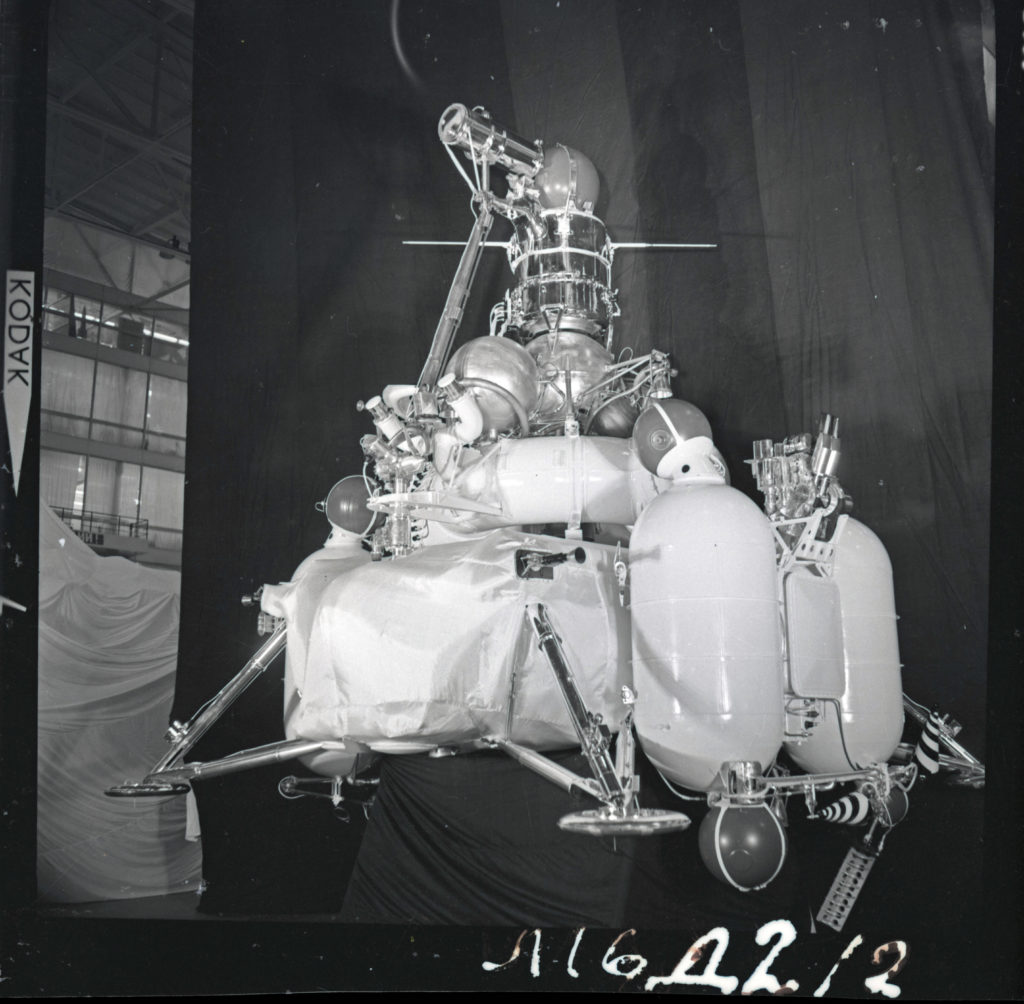

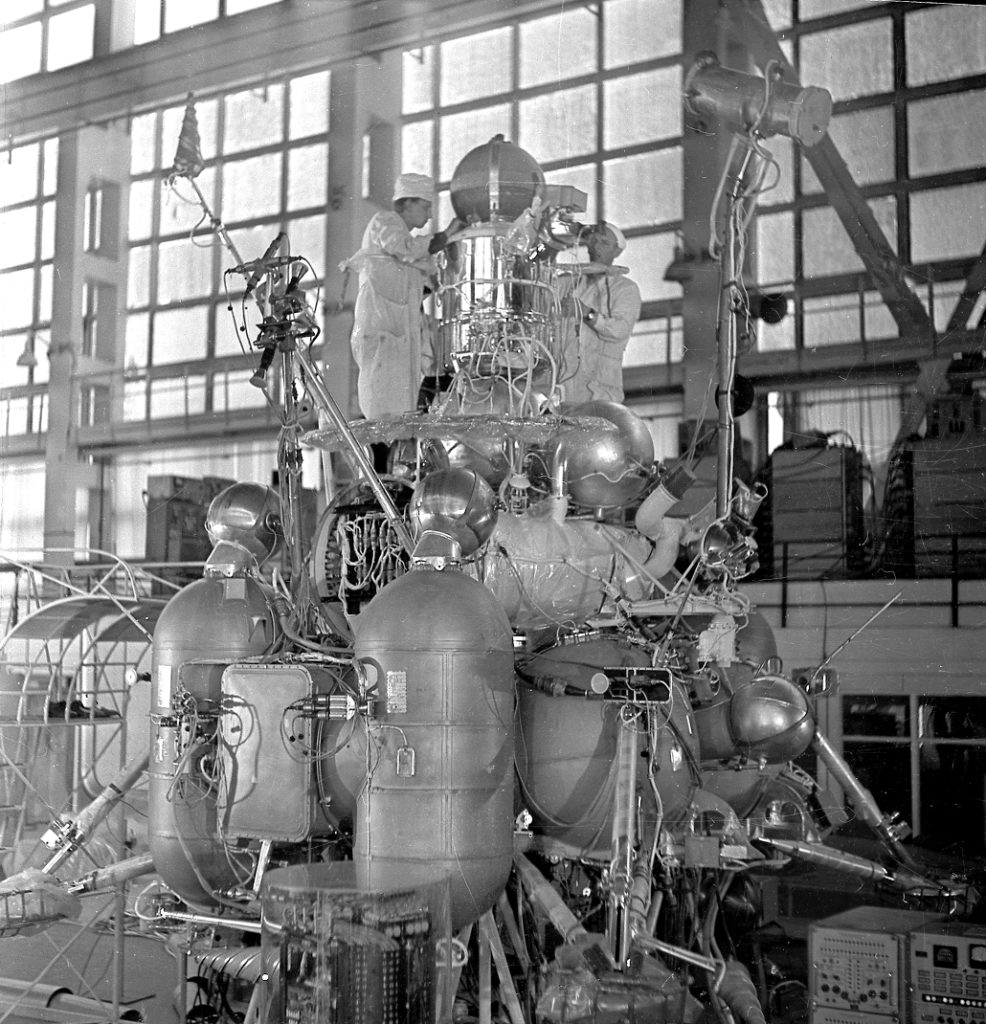

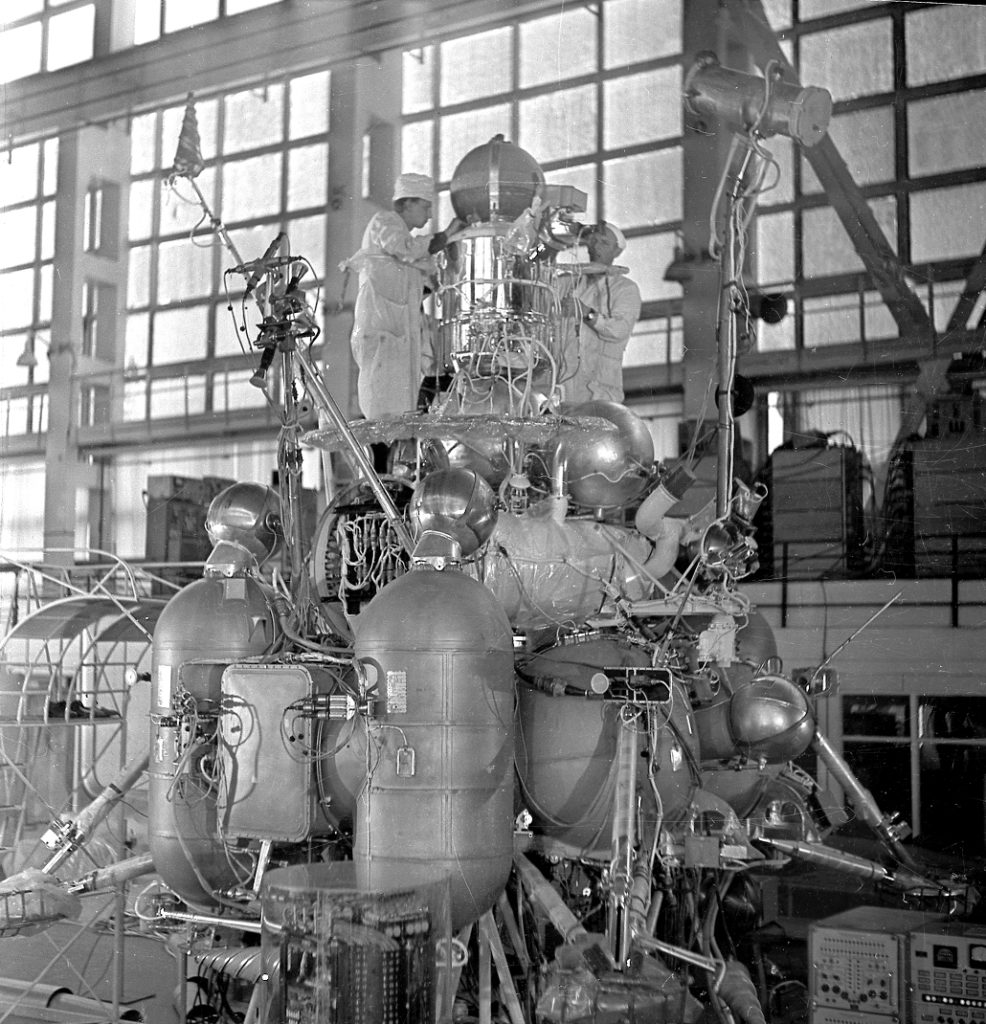

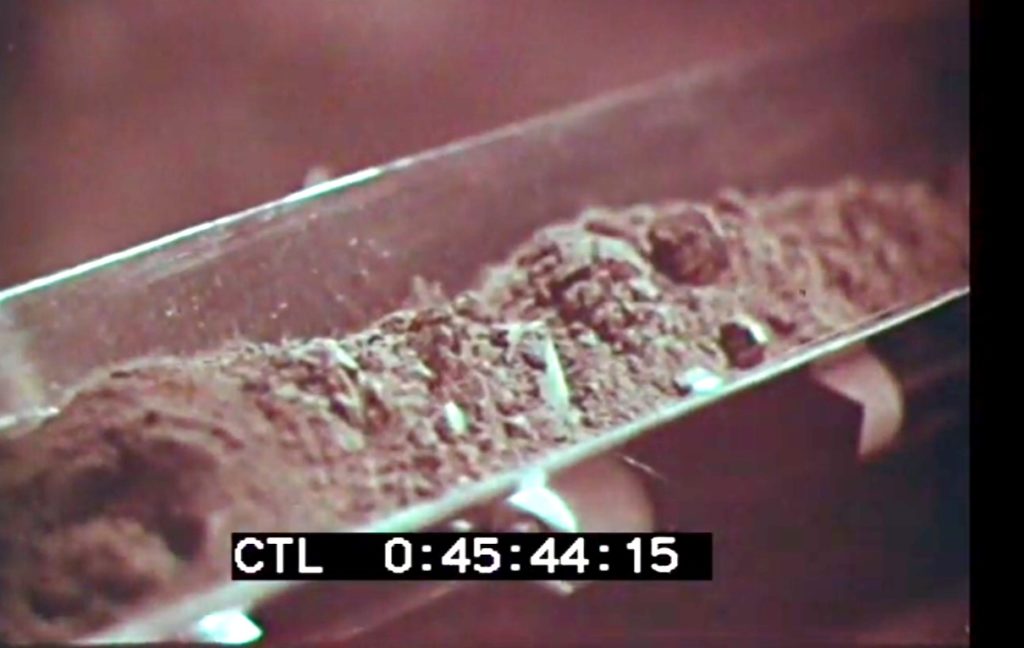

The first major project between the west and USSR was the launch of France’s satellite SRET in 1970 followed by a jointly produced satellite Aureole 1 in December 1971. That success secured additional projects with other European countries. A series of satellites for scientific exploration of the Sun first with joint French series of satellites called Prognoz and later Interkosmos jointly with Sweden. Investigations in Biology (BION – 1973 and 2013) and material science (Foton – 1985 and 2014), Comet, Moon and planetary exploration especially Venus and Mars along with space-based observatories Astron, Kvant, Gamma, Granat and Spektr.

Collaboration allowed European astronauts to get in to space on USSR rockets whereas politics and cost prevented access via USA’s space shuttle just as it became operational. In the 1970s several astronauts from the Warsaw pact countries got a ride to Salyut 6. Jean-Loup Chrétien from France was the first western to arrive on Salyut 7 in 1982 and with a second flight 1988. German, Austrian, and British astronauts followed. The Russian dominance in human spaceflight was highlighted once the Space Shuttle was retired in 2011. From then to 2020 the Russian Soyuz was the only transport to the space station for American astronauts. The author explores almost forgotten four projects for European human spaceflight projects: Hermes, Mir 1.5, Kliper and ACTS, which never came to pass. If they had Europe today would have a “much stronger role in human spaceflight”. Instead, Europe remains devoid of human rated launch vehicle.

Industrial cooperation driven predominantly by commercial and economic interests proved to be the most challenging. Those problems are being addressed today through market competition by the emerging private space sector. Then the launch of communication satellites was particularly lucrative with only the USSR and USA having a foothold from the outset. Europe’s entry with Ariane was made particularly difficult by the USA “refusing to sell fuel for it”. Obstacles and sanctions from Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom) or International Traffic in Arms Regulation. The author highlights the role of the little known CoCom. Whereas ITAR was established to maintain American interests in the USA, CoCom (based in an annexe of the USA embassy in Paris) appears to do the same in the heart of Europe.

Despite the hurdles, Europe and Russia have benefited from decades of cooperation in space. European spacecraft and astronauts continue to be launched by Soyuz; European scientific instruments have explored the solar system courtesy of USSR/Russian spacecraft. The USSR/Russia benefited from European expertise in designing, building operating instruments for space and planetary exploration. USSR then Russia learnt project management approach from Europeans. The Soyuz launch facilities in Kourou, close to the equator is a particularly tangible outcome for Russia, a direct product of decades of Franco-Russian cooperation.

Europe has an admirable history of Interplanetary exploration. The book highlights the central role of Russian launchers in making possible ESA’s Mars Express and Venus Express mission. Soyuz launches have also facilitated Europe’s flagship projects of Copernicus and Galileo. In the final chapter the book outlines the long, convoluted, and costly journey of realising ExoMars. The project has been through several iterations of design and planning to arrive at the orbiter, lander, rover, and sample return objectives. This is one example of international cooperation that now includes the USA too.

This is probably the first English language analysis of the individuals, institutions and early space projects that would eventually lead not just France but Europe to its status as a leader in designing, building and operating complex space infrastructure. In the first chapter, “Early Days” the author refers to John F. Kennedy’s little-known but perhaps most powerful speech on 10 June 1963, Strategy for Peace. It would have been interesting to see the author’s assessment on how collaboration in space has cultivated peace on Earth.