On August 29th, NASA made a significant decision to bring its astronauts back to Earth aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft rather than Boeing’s Starliner. This follows a rocky start to Boeing’s first Crew Flight Test (CFT) spaceflight mission, which launched on June 5th with two NASA astronauts bound for the ISS on an 8-day mission. However, things haven’t gone as planned. Starliner will now return to Earth uncrewed on September 6th, marking a substantial commercial and reputational setback for Boeing. Should a catastrophic failure occur during reentry or landing, it could spell the end of Boeing’s Starliner program altogether.

Boeing has provided abundant assurance that Starliner is safe for a crewed return. After all, they have already returned Starliner from LEO to a safe, soft landing in New Mexico twice, once in 2019 and again in 2022. Why does NASA not feel assured?

There are four critical contributory factors. Perhaps the most visceral is NASA’s 2003 experience with the loss of a crew of seven during the ill-fated space shuttle Columbia’s return to Earth. If there are fatalities, it will be seen as NASA’s failure, not Boeing’s. Secondly, this NASA-Boeing commercial contract is a fixed-price one. Boeing, not NASA, will have to pick up the additional cost necessary to certify Starliner as operational. Thirdly, NASA has an alternative option, something that was not available in 2003: SpaceX. Why should NASA take the risk if it doesn’t have to? Lastly, with a comprehensive understanding of all the intricate and interconnected technical details, NASA knows more than we do and feels it has no other choice.

Multiple Failures

NASA and Boeing have acknowledged “multiple failures,” which is not unusual in a test flight. The previous Starliner flights (in 2019 and 2022) were not without failures. The two main problems with Starliner in this CFT have made it to the public domain: five helium leaks and thruster malfunctions. The helium leaks, known about before launch, were not deemed significant. Starliner arrived and docked successfully with the ISS on June 6th. Boeing engineers assessed the leak rates and concluded that the remaining helium could support 70 hours of free flight, but only seven were required. Starliner had sufficient margin for a safe return trip from the ISS.

Helium pressures the 20 Reaction Control Systems (RCS) for fine attitude control and 28 more powerful Orbital Manoeuvring and Attitude Control (OMAC) thrusters. All 48 are located in 4 units (each with 5 RCS and 7 OMAC) known as doghouses on the Service Module. The thruster malfunctions, specifically understanding their root causes, are the primary concern. When the OMAC thrusters are activated, they generate much more heat than expected. In the confined space of the doghouses, that heat is absorbed by the Teflon seals in the RCS, causing the seals to bulge and potentially disintegrate. The resulting debris can block the oxidizer supply to the RCS, resulting in lower thrust. Boeing engineers have replicated some of these symptoms in their ground tests. The uncertainty associated with repeated bulging of the seals during reentry appears to have motivated NASA to throw in the towel with Starliner. Starliner will return uncrewed on September 6th, and NASA astronauts Barry Wilmore and Suni Williams will return with SpaceX in February 2025.

This is perhaps NASA’s most consequential decision. NASA wanted two independent routes for crewed flights to LEO from the outset. Since the Space Shuttle was retired, NASA has spent about $11 billion on its replacement—the Commercial Crew Development Contracts. The lion’s share is almost equally split (SpaceX $5.5 billion and Boeing $5.1 billion). This includes 6 Boeing missions to the ISS and 14 SpaceX crewed missions to the ISS. SpaceX has completed 13 crewed return missions to the ISS, and Boeing has yet to complete its first.

Corporate Decline?

Following NASA’s decision, SpaceX will exploit Boeing’s uncomfortable reputational and commercial predicament. NASA did not take it lightly, and it was probably not informed solely by the quality of Boeing’s work on Starliner but by a broader recognition of Boeing’s performance over decades.

The first stage of the mighty Saturn V, which powered eight crewed Apollo missions to the Moon, was developed by Boeing engineers. From the same decade, the 1960s, Boeing has been a byword for safe aviation. The Boeing 737 and the 747 Jumbo have impressive safety records, not just in the US but globally. Perhaps the 1997 merger between Boeing and McDonnell Douglas shifted the company culture from safety and quality to profit and dividends. Confidence in the integrity of Boeing’s engineering declined further, with two fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019 of its new 737 Max aircraft, resulting in the loss of 346 lives.

Boeing’s difficulties are not restricted to aviation or Starliner. In early August, NASA’s Office of Inspector General published a report on the status of the Space Launch System (SLS) Block 1B. Boeing is the prime contractor for the SLS Exploration Upper Stage (EUS), where the cost has grown from $962 million to over $2 billion. The report found that Boeing’s quality assurance program is not compliant with NASA’s Quality Management System standard AS9100. Between September 2021 and September 2023, Boeing received 71 Corrective Action Requests and is now facing the prospect of financial penalties for non-compliance with quality control standards.

Critical Reentry

Despite media reports, NASA’s astronauts are not stuck, stranded, or abandoned. As the mission designation, Crew Flight Test, indicates, this is a test flight. Barry Wilmore and Suni Williams are space shuttle veterans. They are in no immediate danger and probably welcome their extended stay in space. It is very rare for a spacecraft that took people to space to return empty. In March 2023, the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft returned to Earth uncrewed following safety concerns with an external cooling radiator on its service module.

The Service Module does not survive reentry, so Boeing engineers will not be able to investigate it further after it has returned to Earth. Firing all 28 thrusters during the uncrewed return will be essential for Boeing to collect additional data to inform the necessary modifications. That step may also result in unpredictable and potentially catastrophic failure. That unlikely event could vindicate NASA’s decision and mark the demise of the Starliner program.

I think Boeing engineers will succeed in returning the CFT safely to Earth. On the current schedule, on September 6th, Starliner will undock from the ISS at 6:04 and land on the 7th at 12:03 EDT. Space is hard for Boeing right now, but it will have moved on in a few years. These profound difficulties will be interesting footnotes in Boeing’s developmental history.

The Moonwalkers: A Journey With Tom Hanks

This post is based on an article that will appear in the Summer 2024 edition of the Newsletter from the Open University Physics and Astronomy Society.

Out of the twelve men with personal experience of walking on the Moon between 1969 and 1972, only 4 remain. It was a unique event in human history that by chance occurred in my lifetime. Carl Sagan’s words captured this exceptional nature saying “In all the history of mankind, there will be only one generation that will be first to explore the Solar System”.

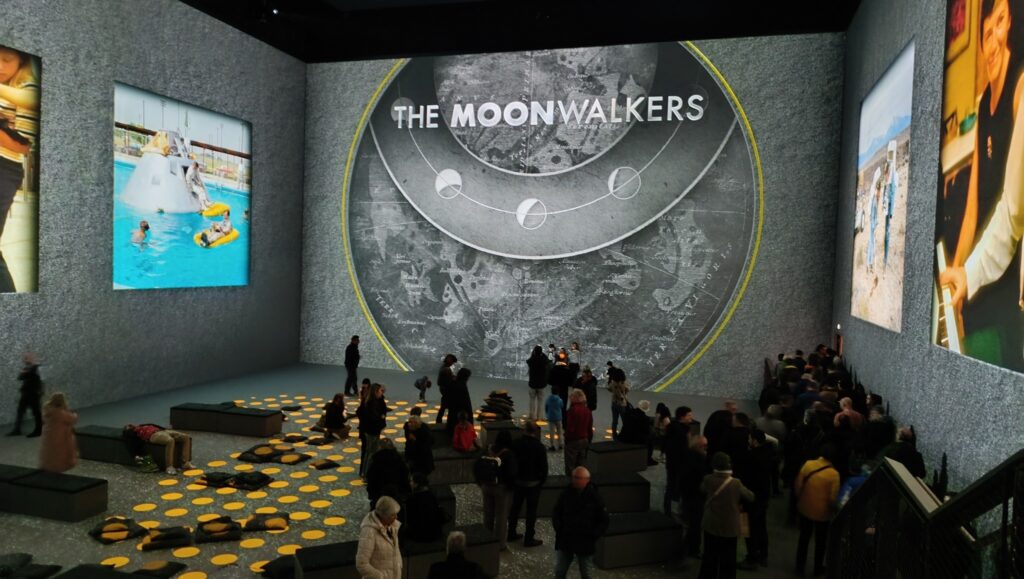

Moonwalkers: A Journey with Tom Hanks is an immersive audio-visual experience in a unique venue in the centre of London. The 50-minute show is centred on the recollection of the then 13-year-old Tom Hanks’ experience of seeing the first men to walk on the surface of another world. The script was written by Tom Hanks and Christopher Riley. Riley is a well-known author and filmmaker, specialising in documentaries on the early phase of the Space Age (i.e. First Orbit available on Youtube and Director’s Cut of Moonwalk One DVD) on Amazon.

The Space Race was a product of the Cold War and ostensibly a race between the mighty political ideologies of Western Capitalism and Eastern Communism. But when it came to the extraordinary achievement, seeing the men walk around the Moon on a tiny black-and-white screen, it transcended national identities and political ideologies. At the time, around a quarter of the USA population (53 million) and around a sixth of the global population (around 650 million) tuned in.

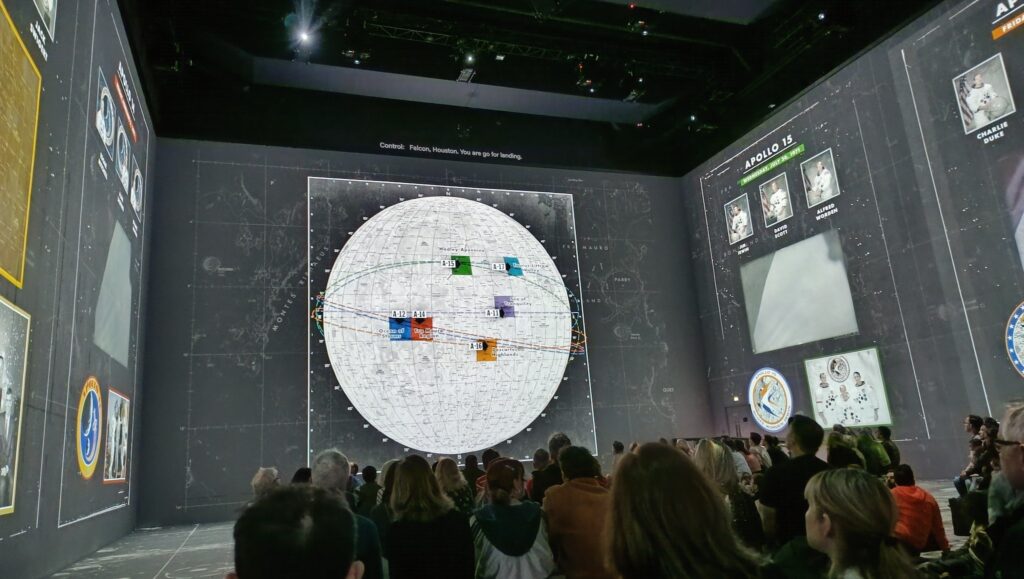

It will not see it Netflix, BBC or even Youtube because the immersive experience only works in a specialised multiscreen venue, like the Lightroom in London. The lightroom is like a large warehouse. During the 50-minute show, multiple projectors dynamically project multiple images on all four walls and the floor. Seating is a series of low-level cushioned benches without a headrest and standalone cushions to sit on the floor. Once the show starts – you have to look all around you – including behind you. Best not to sit too close to the front. Subtitles are included – out of the way at the top of the front wall. Taking the odd picture or video on your phone is not prohibited. I am including here a few of the images and videos I captured during my visit.

Tom Hanks, who has had a fascination with space since childhood, narrates the show. He shares his wonder of experiencing the Moon landing as a teenager. He played Jim Lovell, the commander of the aborted Apollo 13 mission, in his 1995 film – Apollo 13. He co-produced the 1998 12-part drama, From the Earth to the Moon. The series covered the space programme from the Mercury programme to the Apollo 17, the final Apollo mission and went on to win multiple nominations and awards.

The visuals are provided by 26 Panasonic laser projectors but I felt there were many more. The high quality of the images and video was in part the contribution of Andy Saunders, author of Apollo Remastered. He is credited as a Collaborating Producer. He produced the single giant pictures that wraps around multiple walls. Despite two walls meeting at right angles, there is very little sense of distortion. In addition to the video on the main front wall, throughout the show, numerous stills of people, spacecraft and instrumentation are displayed simultaneously. Occasionally with multiple videos. It is the cumulative impact of these multiple threads of audio, stills and video that evoke the emotional response and the immersive experience.

I could not see where the speakers were so assumed they were high up in the ceiling. But not so. Lightroom London is one of three venues around the world kitted out with a German-made Holoplot speaker system. Two panels are embedded, one inside the front and another inside the back wall. Each panel has a matrix array module of 800 speakers each. A little like phased array antennas, the matrix array modules can generate multiple beams of audio, in the vertical and horizontal plane. Just as what you see depends on where you are, what you hear is also finely tuned to location. You are invited to pay once but stay for multiple screenings. If you do – try different locations within the venue. Tom Hanks’s narration, rocket launch and the specially commissioned score by the composer Anne Nikitin provide a lavish emotional experience. The speakers rumble when the Saturn 5 launches and your chest joins in.

The depiction of the Apollo 11 landing sequence was disappointing. I know footage of the descent from the Lunar Module exists but is not shown here. This was a choice to illustrate Mission Control’s limited perspective at this critical phase of the mission. I would also have liked to have seen more footage from the Apollo 13 mission, given Hanks’ back story. I felt the title – Moonwalkers, undercut the contribution of the other 12 astronauts who went to the Moon but never made it down to the surface.

I was surprised to see the long queue but then again I was attending the 4 pm show on a Saturday. I enjoyed it but that was pretty much a given. At the end of my screening, the audience clapped. So I guess most of them did too.

Currently, the Lightroom in London is the only place you can see this but there is a desire to take it elsewhere where suitable venues exist. The £25 per adult (there are concessions) entry is typical of London. But pricey for non-Londoners. They will need to consider the additional cost of travelling to London.

This is a unique opportunity to experience an exceptional achievement of the 20th century played out using 21st-century technology. It is timely. Humans from the Earth are returning to the lunar surface in in the next year or two. . For all the information and to book tickets see Lightroom.uk

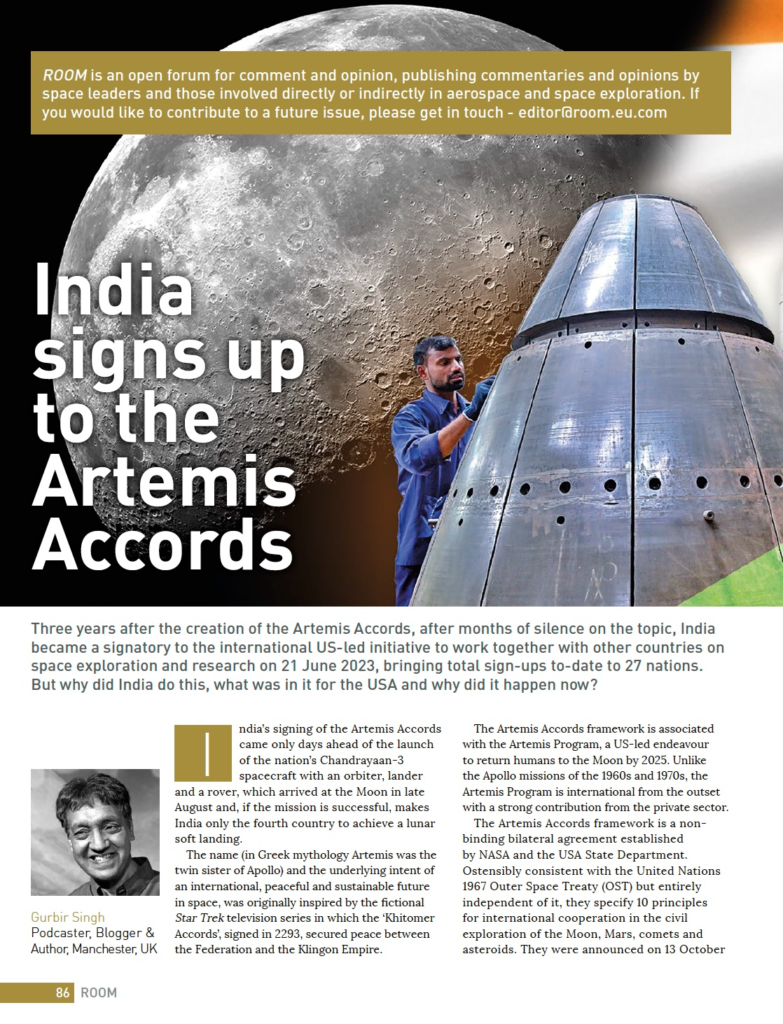

Why India signed the USA’s Artemis Accords and why now?

First published in the Autumn 2023 edition of Room. Space Journal of Asgardia.

Updated 23rd September 2023 – Astrotalkuk.org Read full text online below or download pdf here.

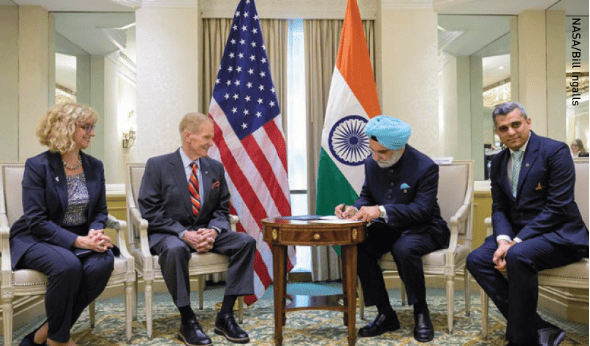

During India’s Prime Minister Modi’s 4-day visit to the USA from 20th to 24th June 2023, India signed the Artemis Accords. Why did India do that, what was in it for the USA and why did it happen then?

The Artemis Accords is a non-binding bilateral agreement (thus not international law) between the USA (NASA and the USA State Department) and each nation that signs up. It specifies 10 principles, ostensibly consistent with the United Nation’s 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST), for international cooperation in the civil exploration of the Moon, Mars, Comets and Asteroids. It was announced on 13th October 2020 during the 71st International Astronautical Congress in Dubai. The initial number of 10 countries (Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States) has gradually grown since. On 22nd June 2023, India made it to 27 countries. Since then Argentina and Germany have signed bringing the total to 29.

Why did India sign when it did? The technologies for commercial exploitation of resources on the Moon and other celestial bodies is now sufficiently mature that every nation that can is rushing headlong to get their stake in the ground. The Moon has a very large deposits of many commercially sought after materials substances for example Helium-3 and Lithium. The technology to mine, refine and transport back to Earth is not yet present. But when it arrives, those nations with a presence on the Moon will be ready.

The number of missions beyond Earth’s orbit, especially to the lunar surface is expected to dramatically increase in this decade. Out of the six lunar landings scheduled in 2023, so far Japan’s (Hakuto-R) failed in April, Russia’s Luna 25 was lost in August. India succeeded with its first soft landing with Chandrayaan-3 on 23rd August 2023. Another from Japan (SLIM), and two NASA commissioned, private sector missions (Nova-C IM-1 and Peregrine) could land before the end of 2023.

As more companies and countries gain a foothold on the Moon, they will benefit from an agreed set of common rules. That is where the Accords come in. The Accords require all countries that sign to abide by a number of principles when operating in space beyond the Earth. The 10 principles include:

1. Peaceful uses: cooperative activities are exclusively for peaceful purposes and in accordance with international law.

2. Transparency: commit to broad dissemination of information regarding their national policies and exploration plans. Agree to share scientific information with the public on a good-faith basis consistent with Article XI of the OST.

3. Interoperability: agree to develop infrastructure to common standards for space hardware and operating procedures that include fuel storage, landing systems, communication, power and docking systems.

4. Emergency Assistance: commit to offering all reasonable efforts to render assistance and comply with the rescue and return agreement as outlined in the OST.

5. Registration of Objects: agree to register and publicly establish which space objects, (on the surface, in orbit or in space) are owned and operated by who.

6: Release of Scientific data: commit to openly sharing scientific data arising from space exploration missions. Not mandatory for private-sector operations.

7. Preserving Outer Space Heritage: undertake to ensure new activities help preserve and do not undermine space heritage sites of historical significance.

8. Space Resources: signatories affirm that extraction of resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the OST.

9. Deconfliction of Space Activities: undertake exploration with due consideration to the UN guidelines for the long-term sustainability of Outer Space Activities as adopted by United Nations Committee for Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) in 2019. Activities, where potential harmful interference could occur, should be restricted to pre-identified Safety Zones. The size, location and nature of operations in a Safety Zone should be notified to all signatories and the UN Secretary-General.

10 Orbital Debris: signatories agree to limit harmful debris in orbit through mission planning that includes selecting flight orbital profiles that minimise conjunction risk, minimising debris release during the operational phase, timely passivation and end-of-life disposal.

The current and next decade will see multiple nations arriving at the Moon, near-Earth asteroids and comets for space exploration and commercial exploitation. The accords define a set of guidelines, principles, and a set of common norms and behaviours that are mutually beneficial when operating missions far from Earth. But why not simply sign up for the United Nations Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Treaty? Whilst the Outer Space Treaty, established in 1967 has 113 signatories, The Moon Treaty (1979), only 18 parties have agreed to be bound by it. India is one of those 18 but has not yet ratified.

Why have so few nations signed up to the Moon Treaty? All to do with the legal status of extracting resources from the Moon. Article I of the OST describes outer space which includes the Moon and other celestial objects as being the “province of all mankind” and “is not subject to national appropriation”. Further, article II in the Moon Treaty explicitly forbids any part of the Moon from becoming the property of a nation, a private organisation or a person. Countries don’t sign up to the OST because they consider it will restrict their future potential commercial operations in space and especially on the lunar surface. The Artemis Accords, on the face of it, offer a workaround. All member nations affirm that extraction of resources “does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the OST.” In other words, you can extract and own the resources but have no claim of ownership of the place from which they came. How legally robust that is, only time will tell. The Artemis Accords (now with 29) already has more signatories than the Moon Treaty (with 18).

But there is another reason why nations may join the Artemis Accords. As the name suggests, The Artemis Accord signatories get to join the already International “Artemis Programme”. What that actually means will depend on the capability each nation can bring to the table. Even a small nation, new entrants like Romania and Rwanda with minimal capability will have access to and opportunities for cooperation. A key benefit of any club membership is access to other members of that club.

Why has India joined only now? Artemis Accords has a competitor. Less than a year after the Artemis Accords were announced, China and Russia established the International Lunar Research Station. The ILRS is a lunar base designed for conducting scientific research. It includes all the support facilities on the lunar surface, in lunar orbit and transport between Earth and the Moon. Two years on, only four nations have joined (Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, South Africa and Venezuela) China and Russia.

India has always remained non-aligned. It has kept its options opened and lipped between USSR, Europe or the USA – wherever its interests were best served at the time. A lesson learnt during the international sanctions regime following India’s nuclear tests in 1974 and 1998. India’s first rocket launched into space in 1963 came from the USA. Its first satellite and first astronaut went to Earth orbit on USSR launch vehicles. India used the Space Shuttle to launch one of its communication satellites in 1983, collaborated with NASA on its first Moon mission in 2007 and is preparing to launch a joint ISRO/NASA Earth observation in 2023. ISRO has launched European satellites and engaged the European Ariane 5 to launch its heavy GEO satellites. Over the last 5 years, Russia has been assisting ISRO with its Gaganyaan (Human Spaceflight) programme.

Sanctions imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine have severely diminished its ability to collaborate in space. Right now and in the foreseeable future, India sees more opportunities with the USA than with Russia.

The geopolitical and economic landscape of mid-2023 was just right for the USA to invite India and India to accept. It was in USA’s interest to get India onboard. It is a win-win situation. As a result, India will have access to technology and know-how for its upcoming high priority Human Spaceflight Programme, Gaganyaan. For the USA, India joining is a huge boost for the Accords which will motivate more countries to join the Accords rather than the ILRS. Setting the Accords on the road to becoming the de facto standard.

The principles of the Accords are said to be “grounded” in the OST and the Moon Agreement, but the Accords is not a United Nations product but has its origins in the USA State Department and NASA. If and when France and Italy sign-up, the Accords will become the default go-to framework for international collaboration in space. In the process, pretty much side-lined the ILRS. A geopolitical win for the USA.

Recognising the importance of India signing the accords, India extracted significant concessions that included space and non-space-related benefits. Although diplomatic ambiguity obscures any direct connection to the significant concessions.

Additional USA-India agreements announced at the same time include :

a NASA/ISRO joint mission to the ISS in 2024 (this tight timeline may not be met but more immediately this may ‘facilitate” NASA support for India’s Gaganyaan programme)

support India’s membership of the Mineral Security Partnership

establish a joint Indo-US mechanism between industry, government and academia for artificial intelligence, information science and quantum information.

A new public-private cooperation forum for the development of advanced communication using 5G and 6G.

A multimillion-dollar investment to establish a semiconductor ecosystem which will include semiconductor assembly and test facilities in India.

In addition to collaborative activities in space, and bilateral economic opportunities, perhaps the most significant concession was the 4 days state visit by India’s prime minister to the USA and the opportunity to address a joint meeting of the US Congress. A public endorsement from the president of the most powerful democracy to the prime minister of the largest one. Particularly useful for a prime minister looking to win a 3rd term in elections in India in 2024. In return, the USA, through India’s membership, boosted the future success of the Artemis Accords and the Artemis Programme.

However, the Artemis Accords are not legally binding. It is not a treaty or an agreement but a set of Accords. There is no compliance or enforcement mechanism. Despite it being a product with roots in one country, currently, it is the only framework that can offer practical value and tangible benefits to all nations with space missions beyond the Earth.

In the USA, the Wolf Amendment legally restricts how NASA can collaborate with Chinese Space missions. Whilst the Wolf Amendment does not legally prohibit China from signing the Accords, in practice that is the effective outcome. Over the last decade, China checked off some astonishing accomplishments in space. Highly successful human space programme, a space station in Earth orbit, a Lunar rover on the far side of the Moon and a soft landing of a rover on the surface of Mars. China sees the Artemis Accords as an instrument to sustain US dominance whilst undermining China’s space ambitions. All this whilst Russia’s space programme has experienced a significant decline resulting from the sanctions following its invasion of Ukraine. Russia may be associated with the heady days of Sputnik and Gagarin but now China has surpassed Russia and is second only to the USA. Whilst the Wolf Amendment remains, it is unlikely in the short term that China will join and thus prevent the Artemis Accords from being adopted as a near-global framework for responsible behaviours in space.

Just as in Star Trek, the Khitomer Accords of 2293 were followed by the Second Khitomer Accords in 2375. So as the Artemis Accords attain wider engagement, they will evolve over time too.

That the Artemis Accords is a product of one country, the USA is its major drawback. To succeed in its ambition to be a global “common set of principles to govern the exploration and use of space” the Artemis Accords require an internationally inclusive appeal. In a decade or two when the Artemis programme exists only in the rear-view mirror of space history, the Artemis Accords could finally become the global governance framework for all nations exploring and exploiting space beyond Earth orbit. The content could remain substantially unchanged but politically transformed with a new name and placed under the auspices of the United Nations.

Episode 108: NASA’s Europa Clipper Mission

The Europa Clipper mission, due for launch in 2024, will arrive and orbit Jupiter in 2030. The third spacecraft to do so after Galileo (in 1995) and Juno (in 2016). The Pioneer and Voyager missions were flybys. The primary objective, as the mission name suggests, is the investigation of Jupiter’s Moon, Europa. Called Europa-Clipper after the 19th-century merchant ships that shuttled between ports at the high-speed then available.

Europa-Clipper will orbit Jupiter, not Europa. This is one of Jupiter’s moons that shows strong evidence of a sub-surface water ocean. During its four-year mission lifetime it will flyby Europa dozens of times looking for conditions suitable for life.

Dr Steven Vance talks about the mission’s goals and current state of readiness. This was recorded in Athens during Cospar 2022. He was the scientific advisor to the 2013 film Europa Report.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:49 — 29.7MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More