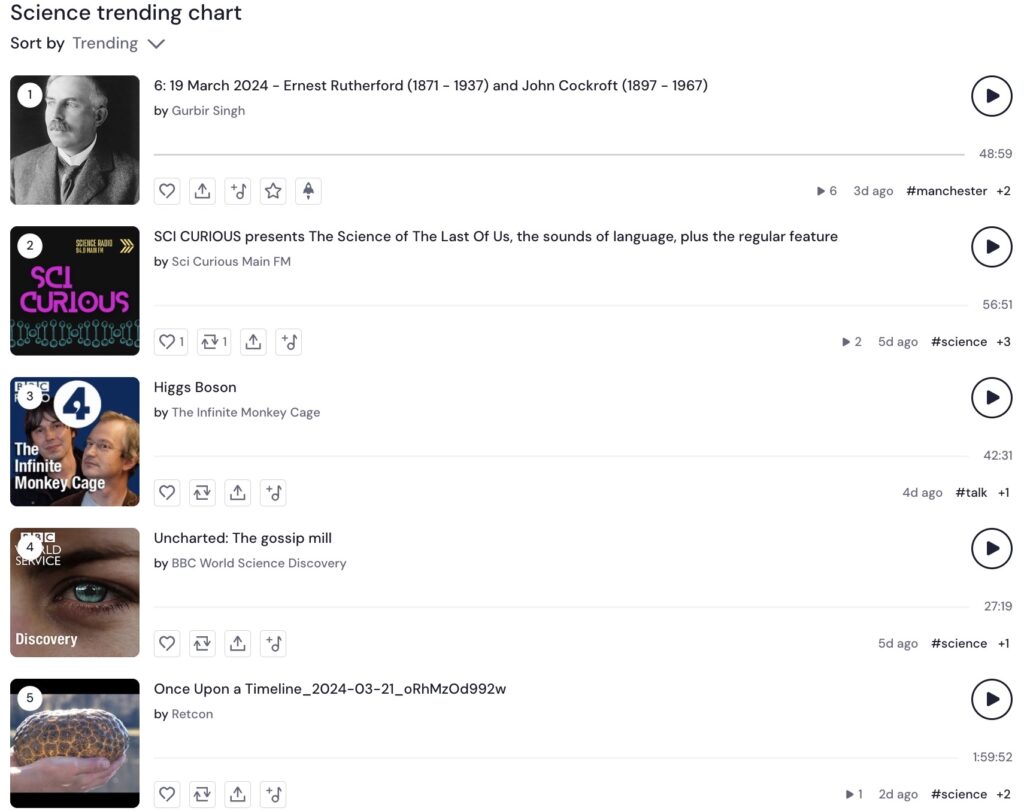

In this episode with Professor Mike Garrett FRS, we discuss some of the many research activities conducted by him, his colleagues and students at the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics (JCBA) University of Manchester. Many of these activities involve international collaboration and are thus conducted elsewhere around the world and not just in Manchester. One of the big takeaways for me was the work of Mancunian Dennis Walsh who made the very first Gravitational Lensing observation from Jodrell Bank. He was also Professor Garrett’s PhD supervisor.

A shorter version of this interview was broadcast on Allfm.org 11th June 2024.

Some of the topics we discussed include:

- Recollections of working with Sir Bernard Lovell

- Gravitational Lensing and its origins at Jodrell Bank through the work of Dennis Walsh

- JBCA’s long association with Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence and how the increased funding via the Breakthrough Listen Programme, has increased SETI research by acquiring more time on existing radio telescopes including Parkes and Greenbank. Also introducing new approaches to SETI research. Rather than collecting new data, the new approach involves analysing open source data from Earth and spaceborne sources including the European Southern Observatory, Alma Observatory and the WISE spacecraft.

- More than 150 individuals from the University of Manchester are associated with the international program the Square Kilometer Array, headquartered in Manchester.

- The global increase in the use of Low-Frequency Array (Lofar) technology in Radio astronomy.

- The USA, Europe and China are looking at the far side of the Moon as a location for radio astronomy

- The role of Brexit and its impact on Britain’s capacity to participate and lead in internationally collaborative programs.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 49:24 — 90.5MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More