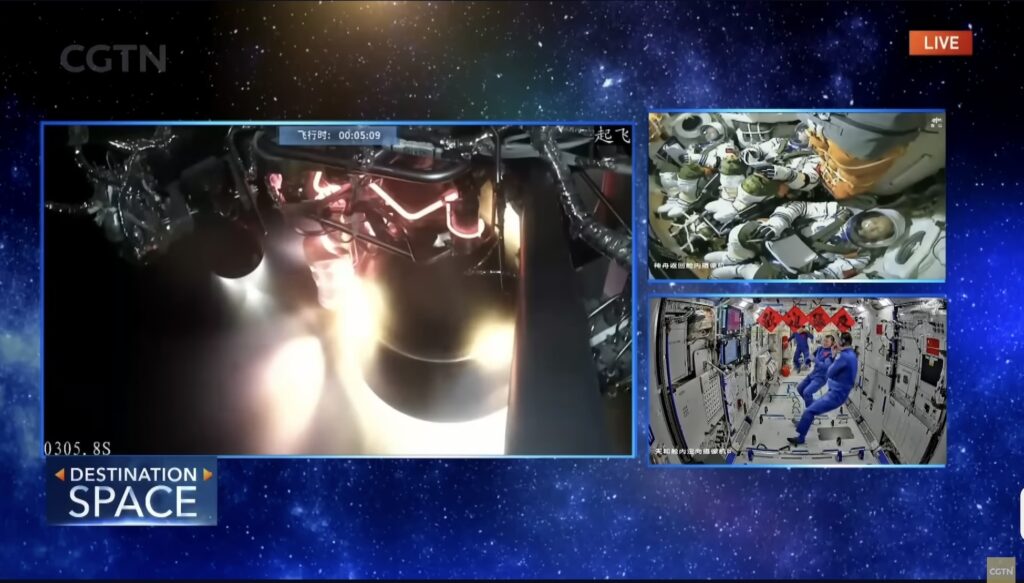

Getting a rocket to dock with an orbiting space station is a huge challenge that requires a deep understanding of celestial mechanics. It is a little (and only a little) like Tom Cruise parachuting from an aircraft onto a moving train. The longer and slower the train, the easier the task. Yesterday’s launch of Shenzhou-21 and docking with the Tiangong Space Station was particularly tricky. A very small train moving extremely fast, but Tom did it!

Yesterday’s launch of Shenzhou-21 carrying a crew of three to the Tiangong Space Station took just over three and a half hours. Previous crewed launches took almost double that, six and a half hours.

Why was it so much quicker? What are the factors that determine the duration between launch and docking and could it be even shorter in the future?

There have now been 16 crewed launches from China’s Shenzhou spacecraft. Shenzhou-5 (15 Oct 2003) to yesterday’s (31 Oct 2025) Shenzhou-21. The first four Shenzhou missions (Shenzhou-1 to Shenzhou-4) were uncrewed test flights designed to validate spacecraft systems, orbital rendezvous, reentry, and recovery.

Typically, these trajectories have taken 1,2, or even 3 days. The concept of a “fast track” trajectory of 6.5 hours was first demonstrated in 2021 with Shenzhou-12.

- 6 h 30 m with five orbits. A routine first employed in 2021

- 3 h 30 m with two orbits. First used on yesterday’s Shenzhou-21

- 1 h 30 m with one orbit. Not yet used, but theoretically possible

Why not always use the fast 6.5-hour or faster 3.5-hour trajectories? Surely, the quicker the crew arrive at the space station, the more efficient the mission. Getting a spacecraft from a stationary point on the surface of the Earth to dock with Tiangong at 400km, moving at 7.67 km/s, is a challenge in precision navigation, guidance, and thrust control. The shorter the trajectory, the higher the required precision.

There are four specific attributes of a safe docking. The shorter the trajectory, the more critical each one becomes

- Launch Window: Can be as short as a few seconds wide. If missed due to weather or unexpected range activities, a full-day launch delay would ensue.

- Orbital Insertion: The launch vehicle’s job is to deliver the payload — here, the crew — to the precise orbit within a few meters per second of the calculated orbit. Corrections may involve missing the rendezvous point, requiring an additional earth orbit to correct.

- Thermal and structural constraints: Short trajectories require rapid orbital manoeuvres and burns, and immediate docking manoeuvres can add unwanted stress to the propulsion system and the crew if manual override is necessary. More complex automated systems are now being deployed with greater confidence.

- Crew stress and safety: The shorter the trajectory, the greater the demand and stress on the crew to ensure a safe ascent, orbital insertion and docking. Also, should an anomaly occur, there is a narrower window to resolve it.

With greater testing, built-in redundancy, and higher precision in navigation, guidance and control, the CNSA has developed the required confidence to use these “fast track” trajectories for crewed flights.

All images from the CGTN YouTube channel – Live launch of Shenzhou-21 https://www.youtube.com/live/uUNigRue9jM