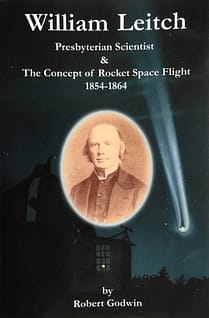

When it comes to the pioneers of rocketry, tradition has it that it was Tsilokosky, Goddard and Oberth. in this episode, author Rob Godwin talks about William Leitch from Scotland. Leitch was writing about the principles of rocket propulsion and space travel in 1861. Decades before Tsiolkovsy. Over the last few years, Rob has been researching Leitch’s story and published a book – William Leitch Presbyterian Scientist & The Concept of Rocket Space Flight 1854-1864

In this interview recorded via Zoom, Rob Godwin recalls how he came across Leitch’s work and the research activity that eventually led him to uncover this remarkable story.

The following 19th-century publications, that Rob refers to are now available online, and pdf versions can be downloaded. Links are available on the episode page

- Half hours in air and sky – Contains the essay “A Journey through Space” P143-168

- Good Words Magazine

- God’s Glory in the Heavens

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 1:09:01 — 55.3MB) | Embed