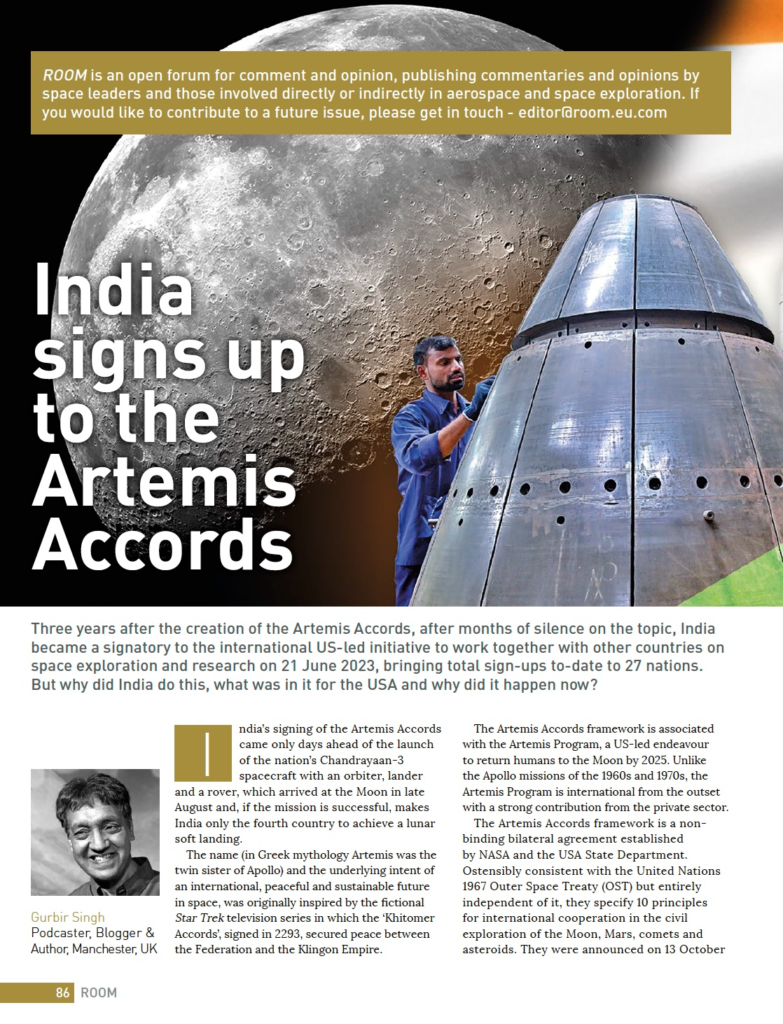

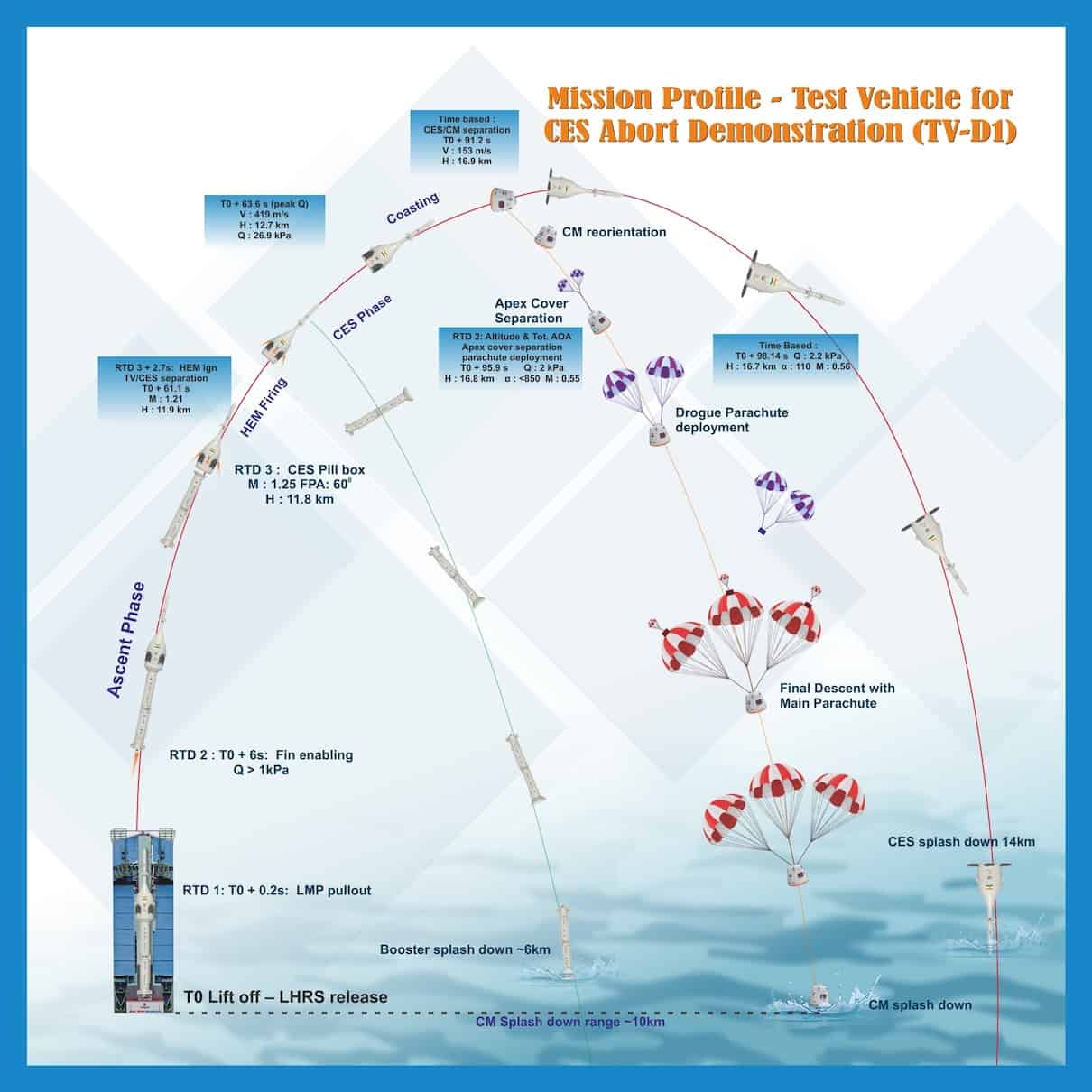

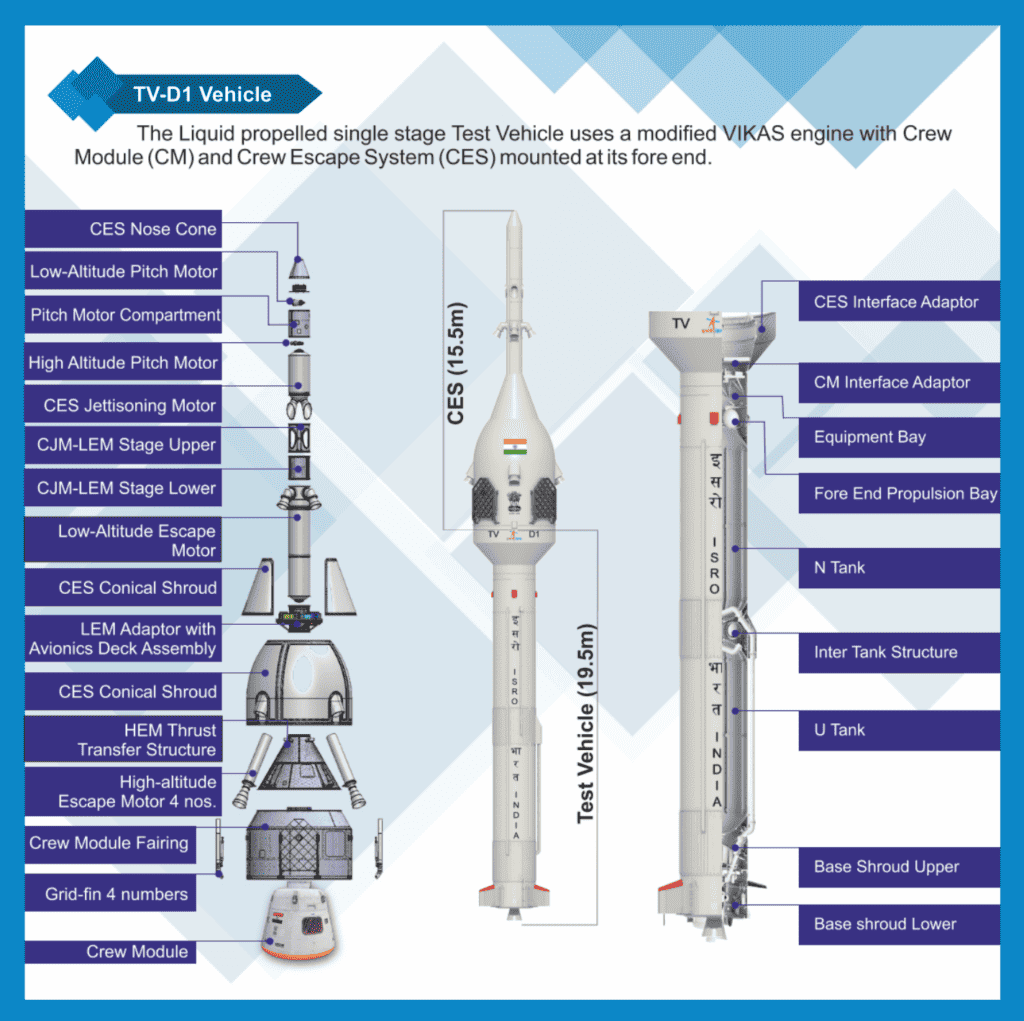

In 2025 India is planning its first spaceflight, carrying a human crew onboard an Indian launch vehicle, launched from India. On 21st October 2023 ISRO conducted an uncrewed in-flight abort test. One minute into the flight, the Crew Escape System fired for just over two seconds pulling the crew module away from the launch vehicle. The momentum took the crew module to an altitude of 17km where the Crew Escape System itself separated from the crew module. Neither the launch vehicle or the Crew Escape System were recovered. The crew module descended to a safe splash down 10km downrange, first using a pair of drogue parachutes and then three main parachutes. About nine minutes after launch the mission concluded having met all the mission objectives successfully.

ISRO concluded this in-flight abort test a complete success despite the poor weather which obscured the launch and the descent. Infrared cameras and the telemetry provided ISRO with the data it required. The ISRO chairman explained that the unexpected hold at T-5s during the first launch attempt was due to the automatic launch sequence detecting a weather threshold breach. The rescheduled launch attempt 45 minutes later was successfully completed despite the crew capsule initially floating upside down. This is not an unexpected outcome for NASA as the Apollo 11 crew capsule was discovered just after splashdown in July 1969. NASA referred to this position as “Stable 2”.

In emergencies ships have lifeboats, aircraft have inflatable evacuation slides. Most crewed launch vehicles heading for space have launch abort or escape systems. They can be activated on the launchpad before launch or soon after launch. Like an ejection seat used by a fighter pilot in an emergency, small but fast acting solid motors separate the crew module from the rest of the launch vehicle for a safe evacuation. Today almost all crewed flights employ a Crew Escape System. Since Yuri Gagarin’s first human spaceflight in 1961, Launch Escape Systems have been activated in three instances and saved the lives of the crew in each case.

In April 1984, Rakesh Sharma, India’s first astronaut, spent a week on board Salyut 7 as part of the USSR’s Interkosmos programme. Six months earlier, on 26 September 1983 Gennady Strekalov, the flight engineer and his commander Vladimir Titov survived the fire that broke out moments before the launch of Soyuz T-10-1. The crew escape system fired, separating the crew module from the inferno that engulfed the launch vehicle seconds later. The crew module landed safely 4 km aways. The commander and engineer were bruised and shaken but fully recovered aided by cigarettes and vodka.

Both Rakesh Sharma and Ravish Malhotra watched this drama unfold in real time, the next Soyuz flight would be theirs. On April 2nd 1984, Gennady Strekalov and Rakesh Sharma were part of the crew launched on the successful Soyuz-T-11 mission to Salyut-7. Sharma and Malhotra had been in training in Star City since September 1982. Both were Indian Airforce test pilots and familiar with the high risk missions. Sharma recalled he did not tell his wife about witnessing this launch failure “as had been my practice right through my flying and testing career”.

Soyuz-T-10 was the second instance, the first took place during the Soyuz 7K-T No.39 mission almost a decade earlier. It was taking a crew of two to the Salyut 4 space station on 5th April 1975. About five minutes after launch, separation between stage two and stage three did not go as planned, compromising the mission. The Soyuz activated the escape system separating the crew module from the launch vehicle. Twenty minutes after launch the crew landed safely in the USSR on a snow covered hill side close to the Chinese border. Thinking they may have landed in China, the crew destroyed sensitive documents associated with the military experiments they intended to conduct in orbit. Thanks to their survival suits and training, they endured the freezing temperature overnight and were recovered on the following day.

The third incident took place on 11 October 2018 when Soyuz M10 experienced a booster separation issue a few minutes after launch. This meant NASA astronaut Nick Hague and Russian cosmonaut Aleksey Ovchinin would not reach their destination, the ISS. The Soyuz initiated the abort, separating the crew module from the launch vehicle and landed safely about 20 minutes after launch. Despite experiencing a force of around 7G, both crew members were safely recovered in good health and returned to Baikonur. MS-12 launched in March 2019 and successfully completed the mission objectives originally planned for the MS-10 mission.

Developing and testing Crew Escape System is one of the many prerequisite critical systems ISRO must develop and demonstrate prior to the first crewed flight. India’s human spaceflight programme has had a chequered history. The first public report of India’s intention to develop a human spaceflight programme came in 2007. The programme was formalised and announced in 2009 but not really funded. At that time, the close relationship between ISRO and Roscosmos was expected to deliver results by 2016. That timeline did not materialise but ISRO has been quietly developing many of the critical systems required for the Gaganyaan programme since. The formal political announcement came from the prime minister on independence day, 15th August 2018. The goal then was the first crewed flight in 2023 to mark India’s 75th year of independence. Many delays including from covid lockdown has shifted the first launch to at least 2025. In the meantime, ISRO has been developing critical technologies including environmental control systems, prototypes of spacesuits and human rating the LVM-3. It has also conducted a drop test of the crew module from a helicopter and the recovery procedure after splashdown.

On 5 July 2018, ISRO conducted a pad abort test. Whilst stationary at the launch pad, the crew module was pulled away to an altitude of about 3 km and safely splashed down less than 5 mins later in the Bay of Bengal. ISRO has conducted two flights that have involved recovering a spacecraft ISRO has launched. During a short 20 minute suborbital flight on 18 December 2014, ISRO conducted the Crew Module Atmospheric Re-entry Experiment (LVM3-X/CARE). This was an experimental sub-orbital flight powered only by the first and second stages of an LVM-3. In January 2007, ISRO launched the Space Recovery Experiment. After 12 days in orbit, the SRE-1 was commanded to reenter allowing ISRO to test procedures for de-orbit, navigation, guidance, thermal protection, parachutes and recovery from a predesignated point in the Indian Ocean. That 2007 recovered module is now in an ISRO museum.

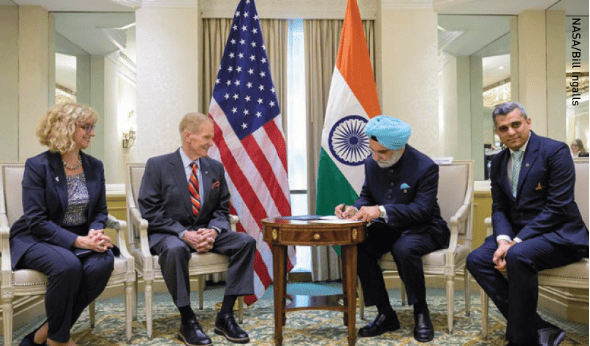

ISRO tends to avoid launches in October when the monsoon season is still active. The poor visibility, the unexpected hold during the first launch attempt, the recovery of the capsule by the Indian Navy from an initially stable 2 position all made a positive contribution to this rehearsal towards an actual crewed mission. In June 2023, India signed NASA’s Artemis Accords. It included a potential flight of an Indian astronaut to the ISS in 2024. It is unlikely but if that happens, the astronaut selected will be one of four Indian Air Force test pilots already trained in Star City in preparation for the Gaganyaan mission. So it may well be that the next Indian astronaut to fly in space will be on the ISS, before Gaganyaan.